IP Portfolio Development: How to Protect your IP

Presented by Greg Grissett, Managing Director, Offit Kurman at the 10x Medical Device Conference – San Diego 2019

Reading Time: 14 minutesGreg Grissett: I’m Greg Grissett. I’m with the Offit Kurman law firm.

I chair the IP practice at the firm. My expertise is in medical devices. It comprises about 70% to 80% of my practice. A lot of it is patent counseling, patent strategy, just helping companies navigate patent issues in a lot of different contexts. We’re going to talk about two of those contexts today.

So part one, just to give everybody an overview of IP and a little bit of a deep dive into patents, what they are, and what they protect specifically.

Part two, is your revenue model protected by your patent strategy? Maybe it’s not question you’d think about from a patent standpoint, but it’s one I like to ask clients.

Part three, what is your risk position with respect to competitor patents? We’re talking about protecting our revenue model, but also mitigating and minimizing risk. And businesses want to know this. Certainly, investors want to know this. Two important issues that you wrestle with as we go through with this.

Part 1: Overview of IP

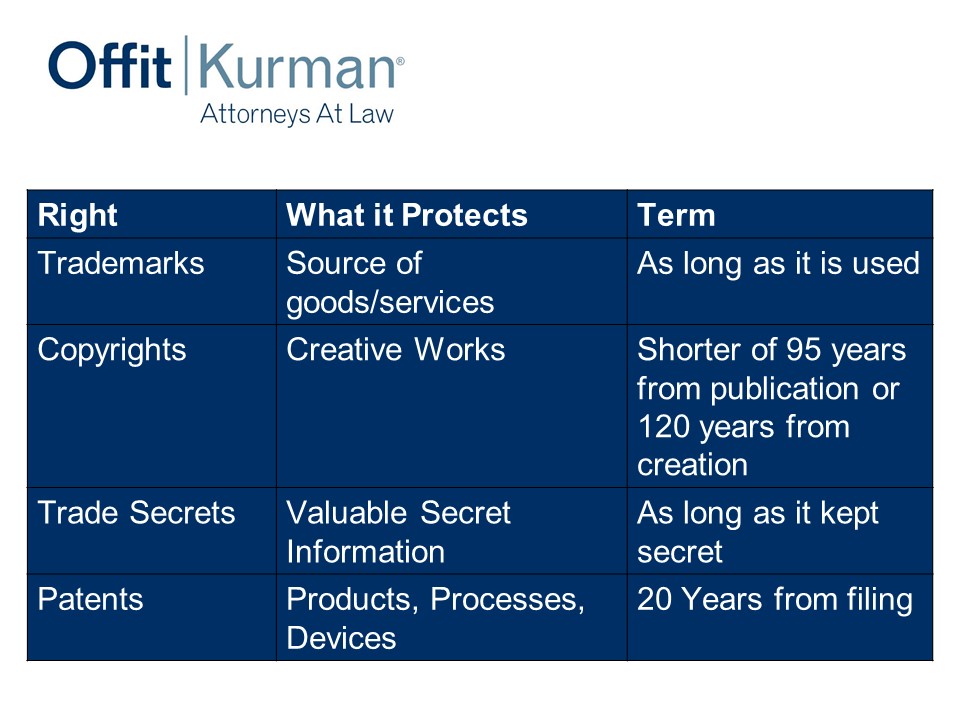

IP classically is really four different rights.

We got:

- Trademarks: This is a source of goods or services. This is really your brands. It’s your brand protection; it’s a word, a logo, or what have you.

- Copyrights: I put here creative works, but the legal definition is a work of authorship fixed in a tangible medium of expression. That sounds very fancy, but it’s art, songs, words, software, software code, user interfaces, your websites, your marketing materials, the things that you express to the world. Either in software form or other mechanisms.

- Trade secrets: Valuable secrets, their value is derived by their not being generally known and you actually taking steps to keep them secret. That’s an important piece. It’s generally the definition that holds across the country but, more or less, it’s got to be valuable because it’s not known and you want to protect it. If you distribute information publicly through social media outlets, you’re not maintaining that as a secret. If you have a manufacturing plant and you’re not limiting access to important parts or not requiring a non-disclosure agreement before your visitors see your manufacturing plant, that’s not taking reasonable steps to protect your secrets, so trade secrets.

- Patents: I put products, processes, devices. This is really the protecting structure and function of what inventors are developing. It could be, of course, pharma products, compositions, medical devices. It ranges to the diagnostic space, to implants and what have you. 20 years from filing is how long patent’s last.

Patents

So let’s dig a little bit more into patents.

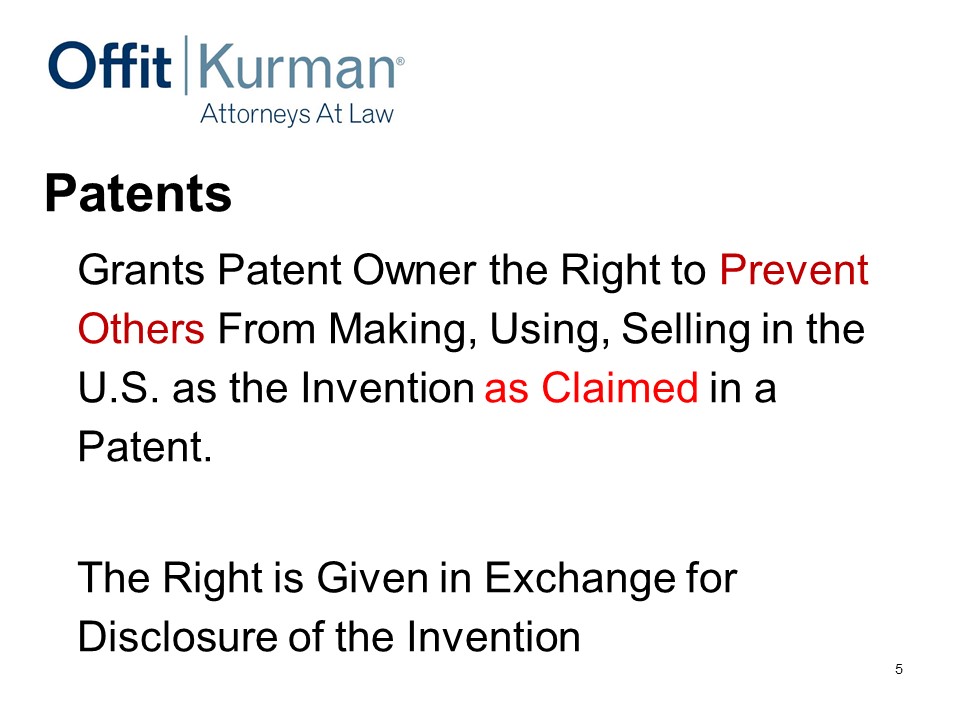

Really important concept to understand for patents – they’re exclusionary rights.

When you get granted a US patent, it gives the owner the right to prevent others from doing all these things in the United States – important here – “as claimed in the patent.”

I like to use the one-acre example. Let’s say I have one acre in Chester County, Pennsylvania, which is where I came from. I have the right to charge you for coming onto my one acre. Same thing, what a patent does.

What a patent doesn’t give me is the right to go into Joe Hage’s one acre in San Diego, all right. So owning a patent doesn’t necessarily give you the right to infringe on other people’s patents. Important distinction, we’ll explore that a little bit more in a bit.

Then again, important here, the right, the patent, is given in exchange for information. Who here has the pleasure of reading patents and patent documents? Okay. So they’re long, they’re dense, and some of them could be vaguely written. But part of the disclosure is the result of having to tell the world about your invention – how to make it, how to use it, and how it might work in a certain setting.

U.S. Patent Claims

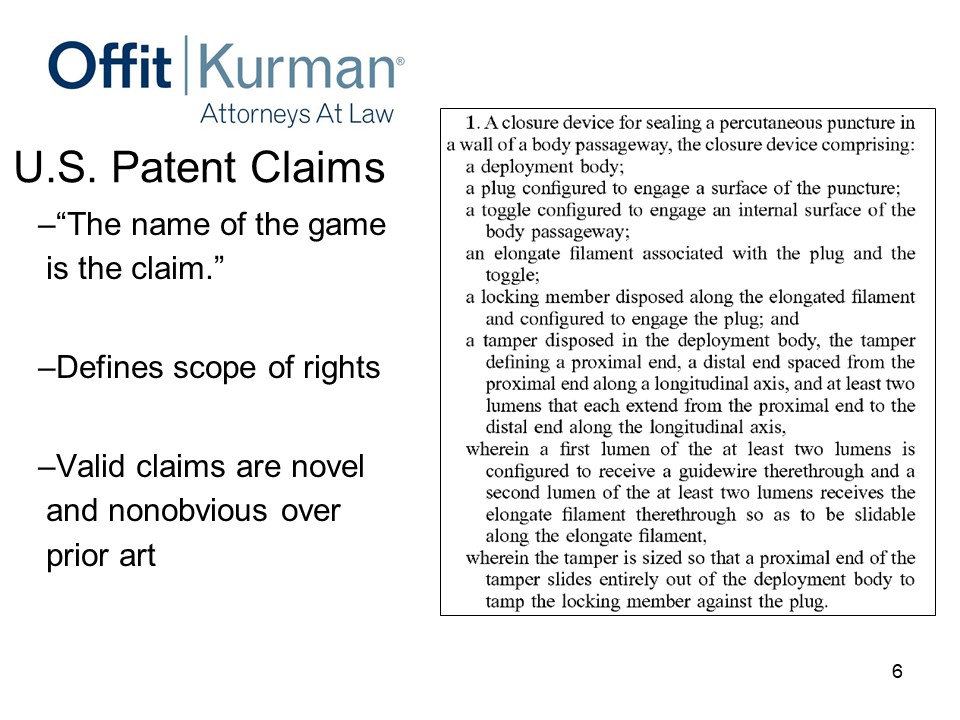

The most important thing you’ve ever read in a patent are the claims at the end. It’s the numbered sentences. This is an example of one at the end of the patent.

The name of the game is the claim. If there’s anything else you read, please read the claims at the end of the patents. That is where the rights are. That defines the scope of the rights.

Important here is valid claims. That’s an important concept. Valid claims are novel and nonobvious over the prior art.

Joe mentioned a good point – what is prior art? Really, it means everything that has come before the time that you filed for your patent. Typically, publications, prior US patents, US patent applications, journal articles, articles that perhaps professors write and publish, that’s all prior art.

Could it be disseminating your product on a Kickstarter campaign? Well, yes, one type of prior art is prior sales. So, if you sell your invention before you file for a patent, you’re foregoing those patent rights. Not such an issue in the medical device context when you have an implantable because you have to go through some more market approval, but it’s important to know.

You can offer your product for sale and that will start the time period.

But the key thing here in the patent is the claim. They define the scope of the rights. This will be important later.

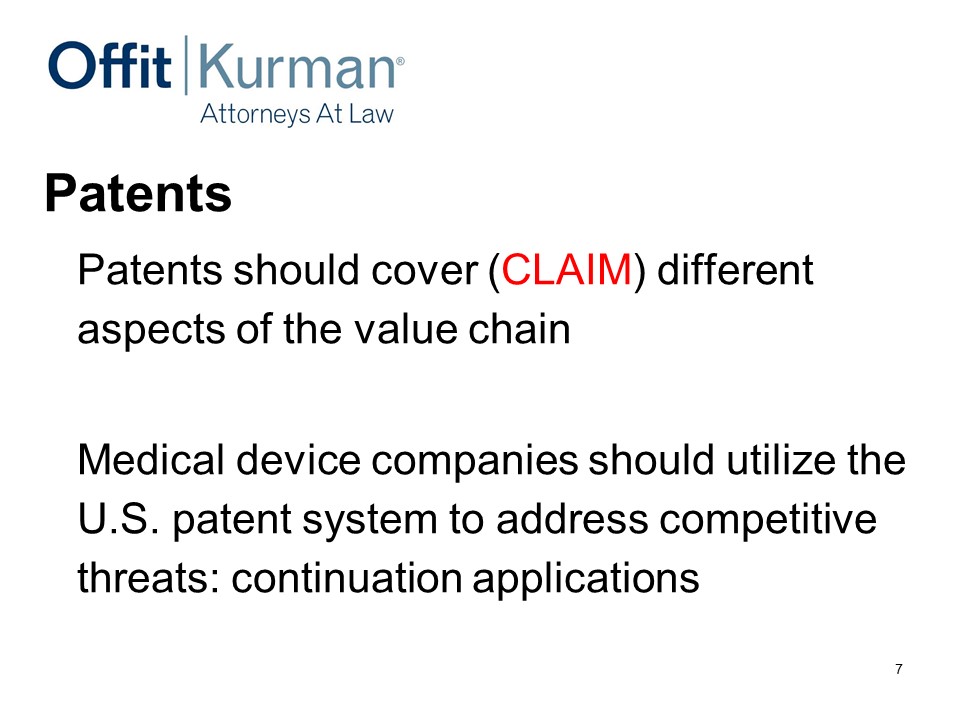

So, in the medical device context, my position and outlook is your patents should cover. And what I mean there, when you hear something or somebody say patents cover, what they really mean is claim different aspects of the value chain in your particular setting.

The other thing that we should think about as we go through this talk is, medical device companies should utilize the US patents system to address competitive threats. I put here “continuation applications” because it’s one area that I see other companies miss the boat sometimes and some companies do it right. We’ll talk about continuation applications a bit more.

Part 2: Is your revenue model protected?

Why am I asking about your revenue model? Well, inventors invent things. They invent technology, and they may develop a new market.

We’ve learned today that, sometimes, you have a problem you solve and you have to create a market around it. The business you’re developing there isn’t direct tied totally to technology. It’s tied to you being able to invoice a company for something and them to pay you on that invoice.

So, when I’m speaking of “are we protecting our revenue model?” your patent strategy should account for what you’re going to generate in terms of revenue in exchange for what you’re invoicing your customers for. An important concept that we’ll dig into more.

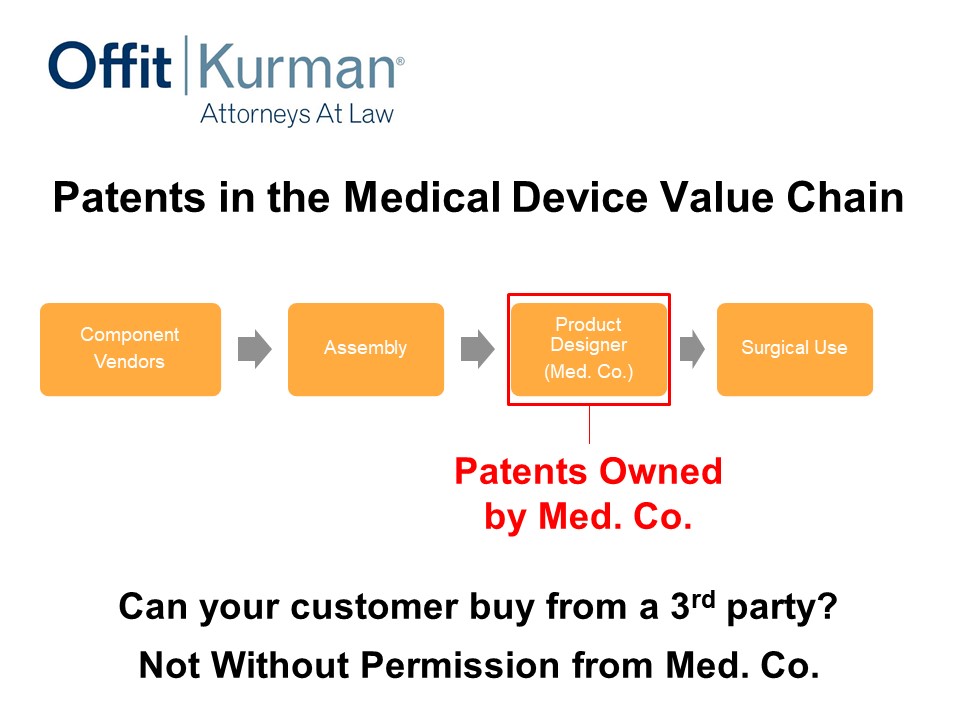

Patents in the Medical Device Value Chain

So this is just a generalized version of a value chain. You may have:

- vendors,

- assembly,

- product designer, our medical device company, let’s just call it Med. Co.,

- surgical use.

This is more in the implantable space, but the value chain you can apply the principles to other contexts.

Let’s say, in this situation, patents are owned and cover the product here as it’s delivered to the hospital system or to the physician. This is a pretty classic scenario. This is, at a minimum, what a company should be doing in the medical device system.

In this example, what you’re shipping to the hospital, you’re going to send the invoice for and what you’re going to get money for, is that which we’re claiming. And the red box in this and the subsequent slides, these are my clients. We want to cover this particular area.

Now, can your customer buy from a third party? Well, practically, not without permission from Med. Co. Now are there other factors in play in the business setting? Of course, but this is just one part of it.

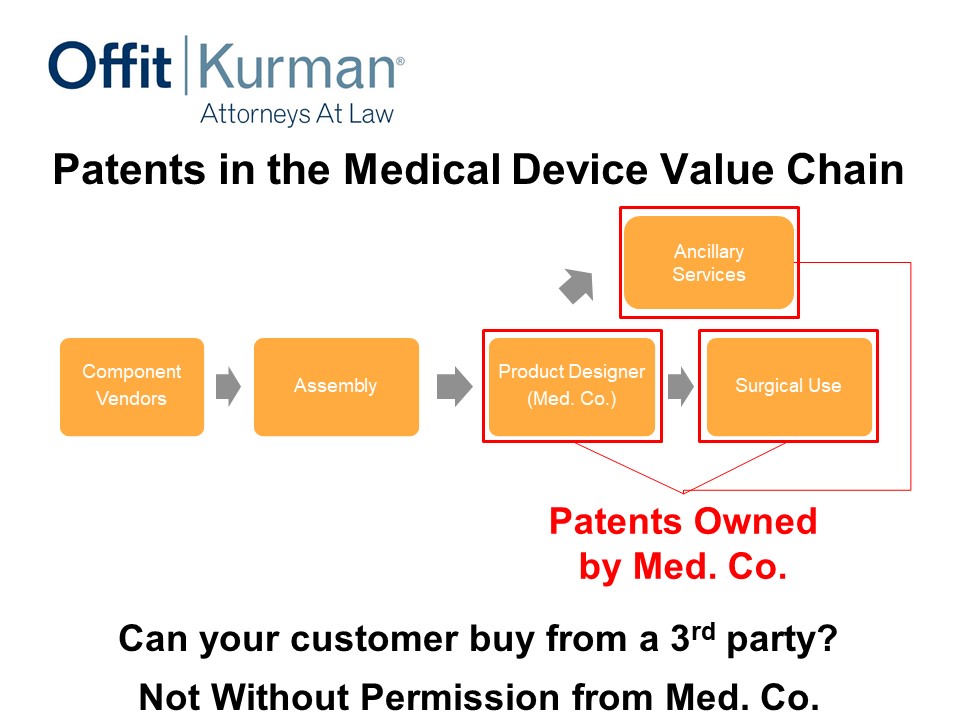

Let’s change the value chain a little bit. We talked earlier today about some ancillary services.

Let’s say Med. Co. device company says, “You know what, I want a little bit more robust protection. Let’s extend our patent coverage into surgical methods, or use of the implant, or use of the product.”

And also, maybe there’s an app or software as a service that we’re offering to the hospital system as an adjunct to the implant and the instruments that we want to sell. We may not be getting revenue for this, but it may help close the deal.

Now what if you had patent protection for that ancillary service as well as surgical use? Now, remember, we’re having claims that, of course, still have to be new and non-obvious over the prior art, But, now, you’re in a position where you’re covering different parts of your value chain in a bit more robust way.

Is this going to cause money to fall from the sky by itself? No. Will it change how a hospital system or your competitors approach the market? I think so. It typically does.

This is a message, really, to the competitors that to really match the value proposition, I’ve got to then design around this ancillary service patent; I’ve got to design around the surgical use patent; I’ve got to design around a product the designer had created. That’s a pretty significant task to do. You’re just making life difficult for competitors.

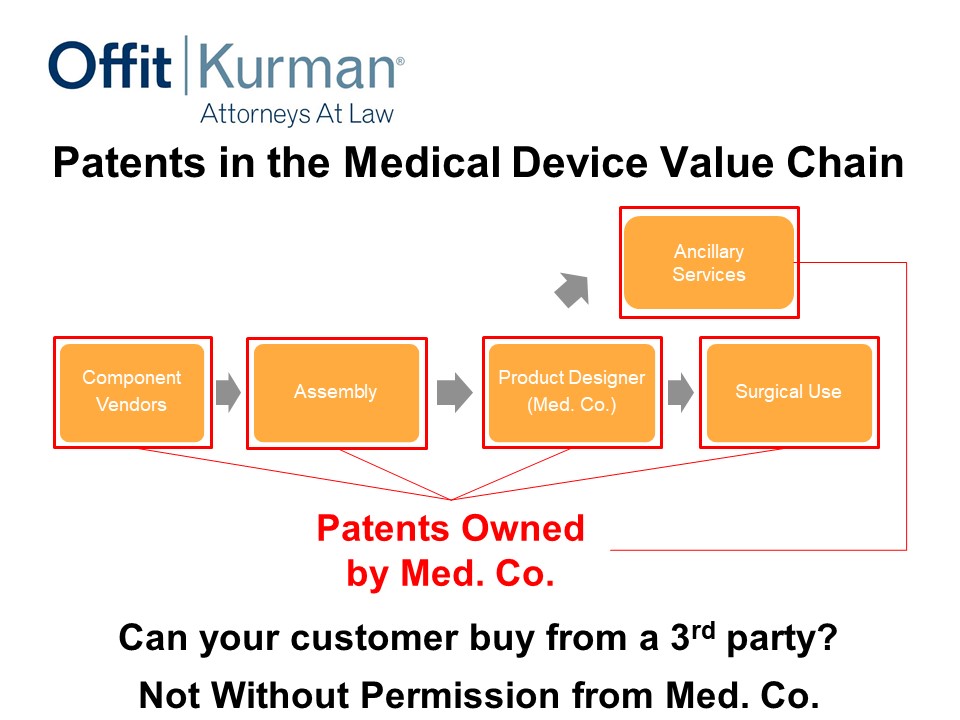

Now let’s go one step further and let’s go backwards into the supply chain. Maybe we can cover some method of assembly in putting the patent together. Maybe we can even go further and down to component vendors.

Now, in this situation, three to five years down the road where you’re offering, you’re generating your revenue, you’re engaging with hospital systems and physicians or what have you, but you’re also protecting your supply chain.

So just think about what type of negotiating position your company may have in this environment. Will it be thing be-all end-all? No, you still have to have good products. You still have to have good clinical outcome. You still have to execute. You still have to have good distribution plans.

But is there anybody in the room that wouldn’t like to have a little bit more leverage when you go to the negotiating table with customers or suppliers? Having source protection this far back in the supply chain can give you some comfort. It will make your supply chain professionals probably rest a little bit more easy at night.

Another thing I’ll ask here, could your component vendor sell their product to a third party if you cover their technology? Not without permission.

So, in this context you can see how patents can be used a little bit further back in the supply chain just to help with your business.

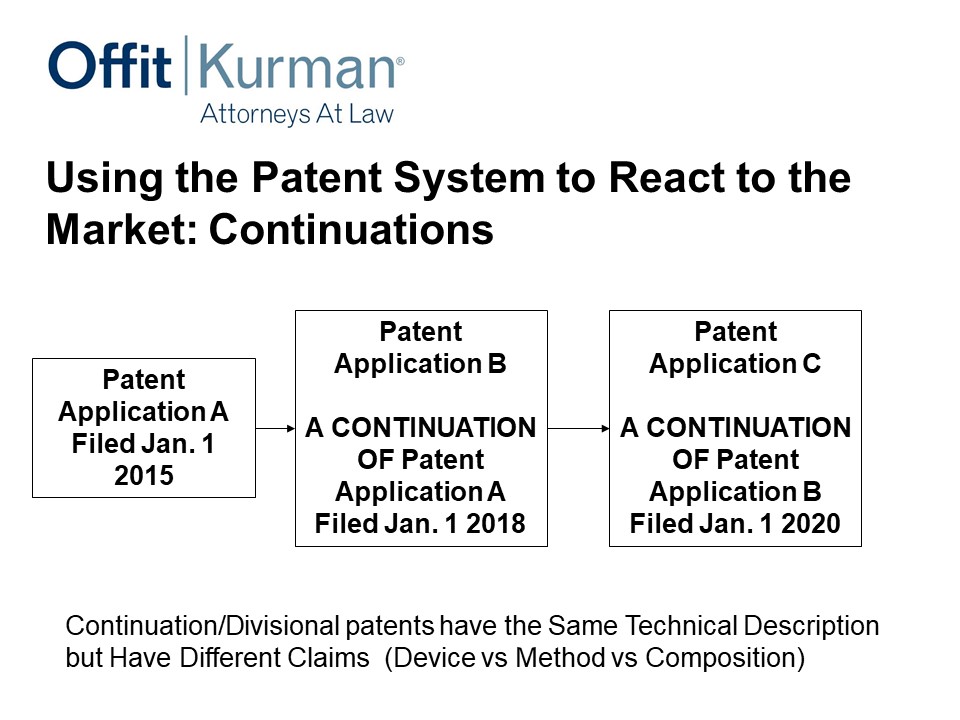

Using the Patent System to React to the Market: Continuations

Okay, switching gears to continuations.

How can we use the patent system to address competitive threats and just the dynamics of the marketplace? You introduce a product, somebody’s going to copy you or copy the essentials of what you’re doing or copy a competing product. How do we address that?

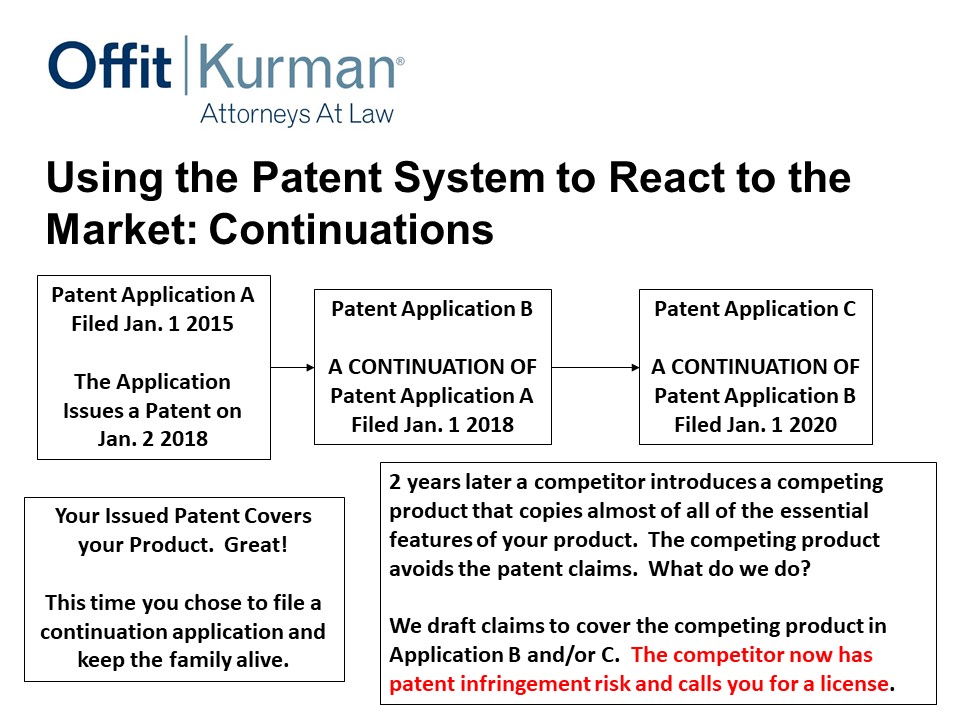

Well, in the US, thankfully, you can file this first application, and before it actually matures into a US patent, you can file what we call a continuation. And that’s if you file January 1, 2018. Two years later, while this is still pending, you can file another continuation.

This strategy can be used for as long as there is patent term available. Large medical device companies do it. I think smart companies that have the resources and the ability to invest in IP in a robust way do this. And we’ll go through some examples of why this is important.

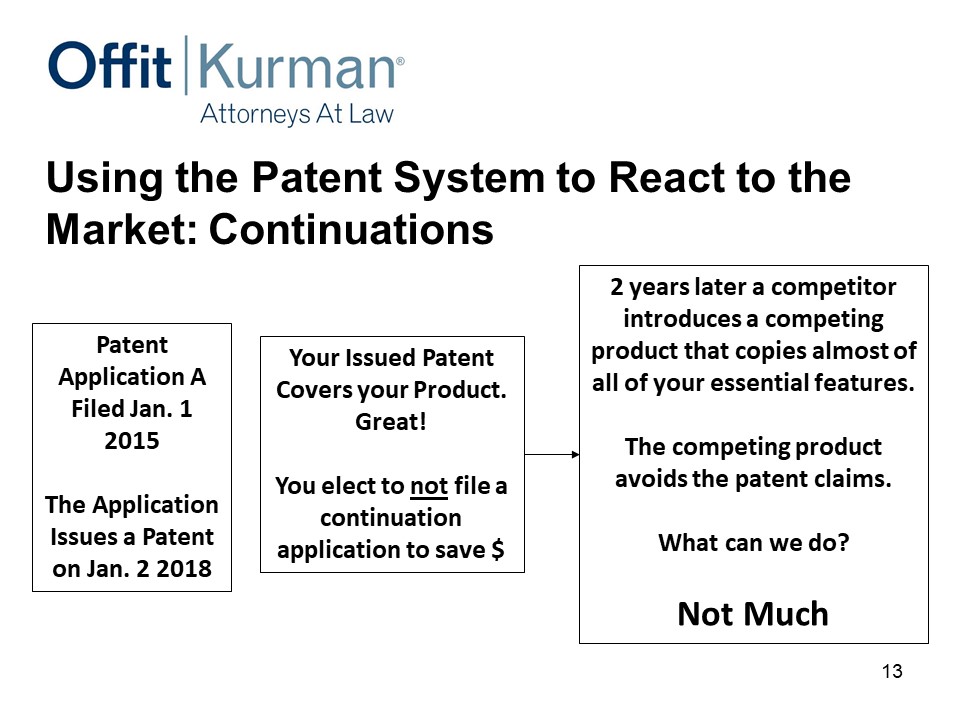

All right, you file patent application A, January 1, 2015. The application issues as a patent, January 2, 2018. Your patent covers your product, great. Maybe you even have some patents back in the supply chain or use patents, but you elect not to file a continuation to save money. And we’re talking 4-6000 dollars to file a continuation application.

Two years later, this one happened, introduces a competing product that copies almost all of your essential features. Not quite everything, but just enough to get a similar clinical outcome at a price that’s competitive. The competing product somehow avoids the patent claims.

Well, there’s two conversations you’ve got to have. One is, what do we do? And, then, how did we miss it?

Sometimes you can’t anticipate what your competitors will do and how they modify or change your product. Sometimes, technology changes and shifts the underlying groundwork you’ve been working with. Well, in this case, from a patent standpoint, I can’t really do much to help. You’ve got patents that don’t cover anything.

Let’s fast forward a bit. Same scenario – you file continuations, you’ve got a patent that covers your product, but now you’ve got some continuations pending. Competitor comes, copies the essential features of what it is issued. What do you do?

Well, now my client can come to me and say, “Look, we’ve got a competitor that’s entered the market, what can we do?” I go check, I look at our continuation, I draft patent claims. Now that competitor has patent infringement risk that they didn’t have before.

So continuations are business tools to use to help you protect what you’re investing in.

Protect as much of the value chain as you can, and make use of continuations to react to the market. That’s what you need to learn from part two.

Part 3: Avoiding IP Infringement.

This is about risk mitigation and reducing the expense of dealing with patent infringement risk.

Often, I get a question like this – You develop a product and you’re close to market. You haven’t done a patent search. You don’t know what’s out there. What do you do?

Freedom to Operate (FTO) study

We’re talking about freedom to operate studies here – what they are and when you should do them.

Importantly, this is a search and analysis of patents to determine the risk of patent infringement for marketing a product or service in the US.

Important here that FTO and patent infringement is about the commercial product. It has nothing to do in essence with your own patents. It’s all about what you’re selling in the US.

Why do you do this? Well, you want to know if you infringe a third party’s patents. Some of this is just practical information. That’s the business reason you would do a FTO.

There’s a legal reason. If you get sued for patent infringement and you’re found to infringe and you can’t prove the patents are invalid, the judge can say, “You know what, you wilfully infringed that patent. We’re going to triple damages.” Well, your freedom to operate opinion can be introduced as evidence to minimize that by a third.

So that’s the legal reason we would have a freedom to operate opinion. That is reducing damages awarded that could be significant.

Then again, investors want freedom to operate. Investors don’t want to buy a lawsuit. Freedom to operate gives you an idea of how to assess that.

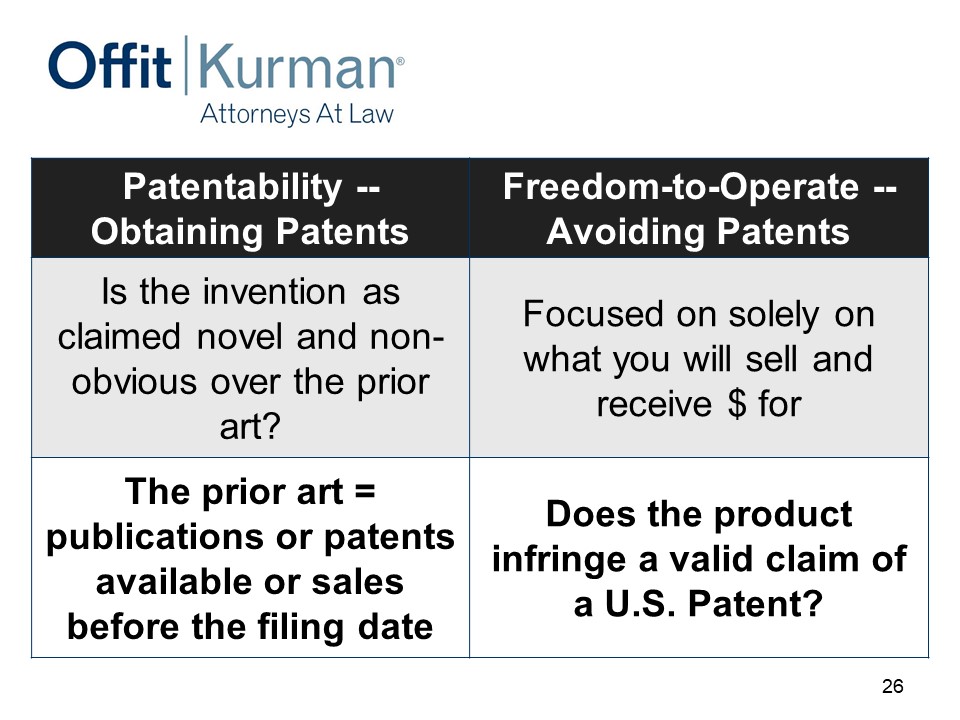

This chart is available, I won’t go through it, but the idea here is, you only have risk of patent infringement when you infringe a patent that is actually valid.

So the freedom to operate study is about investigating those two things – infringement and validity – separately.

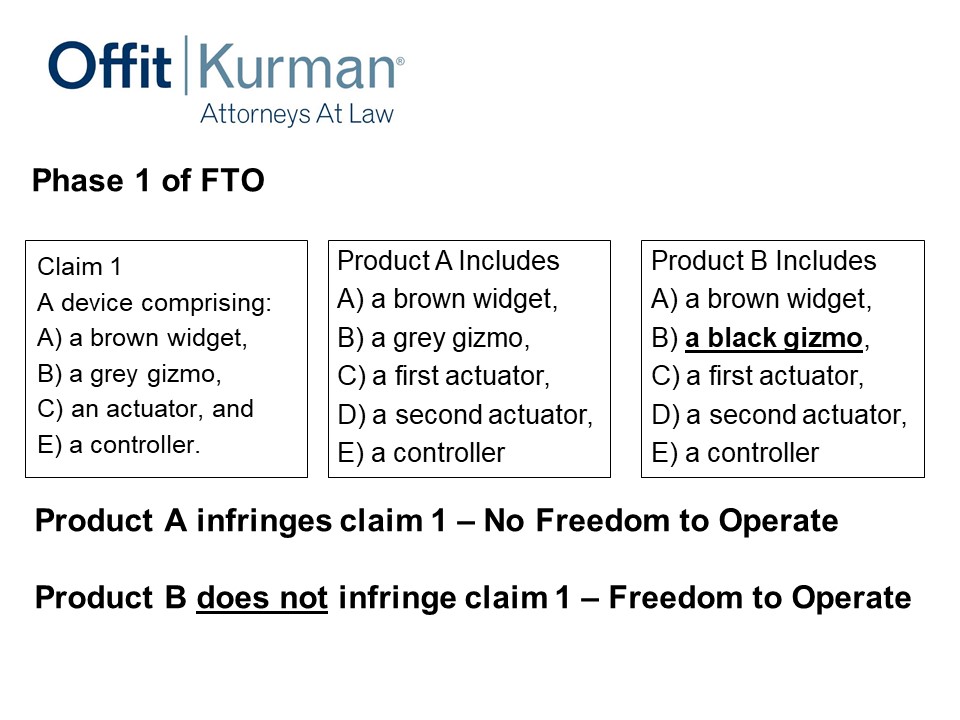

Now, phase one of the FTO. Let’s say the patent claim has a device comprising a brown widget, a gray gizmo, an actuator, and a controller.

You come to me with product A – it has a brown widget, a gray gizmo, a first actuator. And you’re like, “Look, we added a second actuator – I don’t want to infringe the patent – and a controller.”

Well, actually you do. Product A infringes Claim 1 because product A has everything that Claim 1 requires. I’m talking about product A. I’m not looking at your patent applications that cover product A. I’m looking at what you’re going to make and sell.

Well, let’s think about what we could to change it. We’re doing a design-around analysis here. What can we change? The engineer comes back and says, “You know what? Our gizmo doesn’t need to be gray, it can be black,” so you change it.

Right now, product B doesn’t infringe. I don’t have literal patent infringement there, and I’ve avoided that patent risk. You wouldn’t know that if you hadn’t done the FTO study. You wouldn’t know that unless you had your counsel look at this issue in some detail.

Incidentally, maybe this black gizmo is patentable in and of itself. So, you’ve done a design-around of the competitor’s patents, and you’ve identified subject matter that can increase your patent asset. Maybe changing from gray to black is not that special, but it’s worth at least looking at it.

The other thing to keep in mind here is, this design-around you may patent – if you do get a patent for it – is also preventing third parties from adopting that design around. So you are staking out claims to the design arounds you’re doing when you’re avoiding patents.

Patent litigation

Just a big summary – why FTOs are important is really at the bottom here.

25 million dollars at stake. Patent infringement through trial costs you two and half million dollars. That’s both sides. That’s a lot to stomach when you’re applying if ever you want to go after somebody, but you also have to know the defendant has the same pressure that you will. And this is a tool you can use.

These are recent statistics from 2017.

Conduct FTO Study at the Right Time

When do you do a FTO study? This is a hard question, I’ll be honest.

It should be after something that’s very basic and conceptual, but it should before you’re about to order millions of dollars’ worth of components to assemble products, or you have a large capital outlay, or somewhere near your submitting your products for clinical trial, because you want to know.

If I get a product approved that still infringes a patent, that doesn’t necessarily help your risk position. So you want to do that some time ahead.

Usually, I’ll tell people, if you don’t have solid models and you don’t a bill of material, a real bill of material, then a freedom to operate is a little premature. You need to be that commercially detailed because you want to have some sense that this is what you’re going to make and sell.

The other part is, what are substantial product changes? It can be different for different companies. But if there’s a significant product change, your risk position could change, and you want to assess that.

The important thing is to build this into your pipeline, build this into the way that you’re innovating your products, so that you’re addressing these points from time to time.

Summary

Patentability, obtaining patents – this is about protecting your revenue model, and part one is an assessment of prior art and the publications.

Freedom to operate is about avoiding patents, focused solely on what you will sell and receive money for.

Q&A

Joe Hage: What do you do if somebody just doesn’t play by the rules?

You put a patent but, perhaps, – just because they’re so easily maligned – China sees it and they knock off. What’s your real recourse here?

Greg Grissett: Well, you’ve got to have the tools in place to have recourse, number one.

Even if you’re worried about actors in China, typically they still have to import into the US. And under US patent law, if you can prove infringement, you can stop goods at a port. That is pretty significant.

No business manager, whether they’re in China or in the US, wants to deal with their goods being held up at Long Beach.

Man: Really great talk, thanks for that.

I just have a question about patenting up the food chain, so components and assembly methods and that sort of thing.

I definitely agree with it, but how practically enforceable are those patents? I can see your finished medical device or your molecule, but I can’t necessarily see how you got there, unless I happen to be in your factory.

Greg Grissett: So there are some generalizations here, but I’ll give you maybe an example about a spinal implant that’s made of three special polymer blends and you blend them together and you put them together in an interesting way.

I have, probably, patent protection for the implant, regardless of what it’s made of. But maybe I can still seek patent protection for these specific polymer blends as a composition.

Now how do you detect and enforcement? That’s a challenge for every industry. Often, we get information that trickles up from the sales people and the sales group and just generally information that comes around.

If you get your hands on a sample, you can test it. Part of my job when we’re drafting these patent claims is to make sure we can assess a device. If I have an implant right here or I have a sample of a polymer blend, that we can send it to a lab and that report will validate that it infringes the claim.

So some of that is just being crafty and thoughtful when you’re drafting your patents.

Joe Hage: Greg, I want to thank you again for being a sponsor because, as I’ve shared, there are some folks here in the audience who otherwise might not have been here had it not been for your support.

So thank you very much, Greg Grissett.

(audience clapping)

Recent Comments